Khulisa’s Jennifer Bisgard and Nicola Theunissen contributed an article on M&E to Trialogue’s CSI Handbook 20th Edition. We feature the article as it appeared in the Handbook.

The business rationale behind better M&E practice cuts across all spheres of Corporate Social Investment(CSI) initiatives. Managers and directors want data-driven decisions. Stakeholders want to collaborate with projects that work. Programme managers want to publicise their successes, reach and impact, and demonstrate accountability. Companies want to invest money in projects that produce good results. Everybody wants to learn from the process, with the goal of improving their programme. Theoretically, M&E offers the ultimate organisational win-win.

However, as CSI managers move from the boardroom decision to monitor and evaluate, to the reality on the ground, they often find themselves navigating through unfamiliar territory and unforeseen obstacles. The most important differences between monitoring and evaluation are the underlying processes. Monitoring is a routine job that entails the diligent collection and analysis of data for a project’s inputs, outputs, activities and short-term outcomes. It is best used when compared to specific targets and expectations.

Evaluation, on the other hand, is often retrospective. It is the process during which the proof of concept is assessed, or a project’s achievements are measured, against its objectives and intended impact. It’s the ‘catch-your-breath-and-reflect’ moment in a programme’s lifecycle, during which you must interrogate whether you are achieving your objectives.

Moving from faith to facts

Although the corporate sector has made inroads over the past 10 years, several CSI projects and programmes still comprise weak M&E systems which do not provide ongoing feedback and fall prey to obvious pitfalls. Private companies are lagging behind donors, especially international foundations, bilateral and multilateral funders. In the corporate sector, Khulisa Management Services often comes across faith-based development.

People may have a deep conviction that what they are doing is making a difference. However, if you do not put some distance between yourself and the cause, and punch holes into the concept, in all likelihood you will have a project that looks great on paper, but has no impact on the ground. Evaluators should be thought of as critical friends – people who understand that CSI managers are trying to make a difference with their whole hearts and that is not what is being questioned.

M&E is not a faultfinding mission, and it does not question an organisation’s altruism or integrity. Rather, M&E is about adapting the approaches – using what works, discarding what doesn’t – to improve the project’s outcomes and impact. Since money is scarce, you want to guarantee targeted social interventions that align with your organisation’s business strategy and give the board some indication of return on investment; but where do you start? Standing in front of a blank canvas, ready to paint the first shapes, lines and colours of your M&E strategy may seem as overwhelming as it is exciting. The best foundation for planning and implementing M&E is to begin with the tried and tested ‘theory of change’.

Unpacking your programme’s ‘so what?’

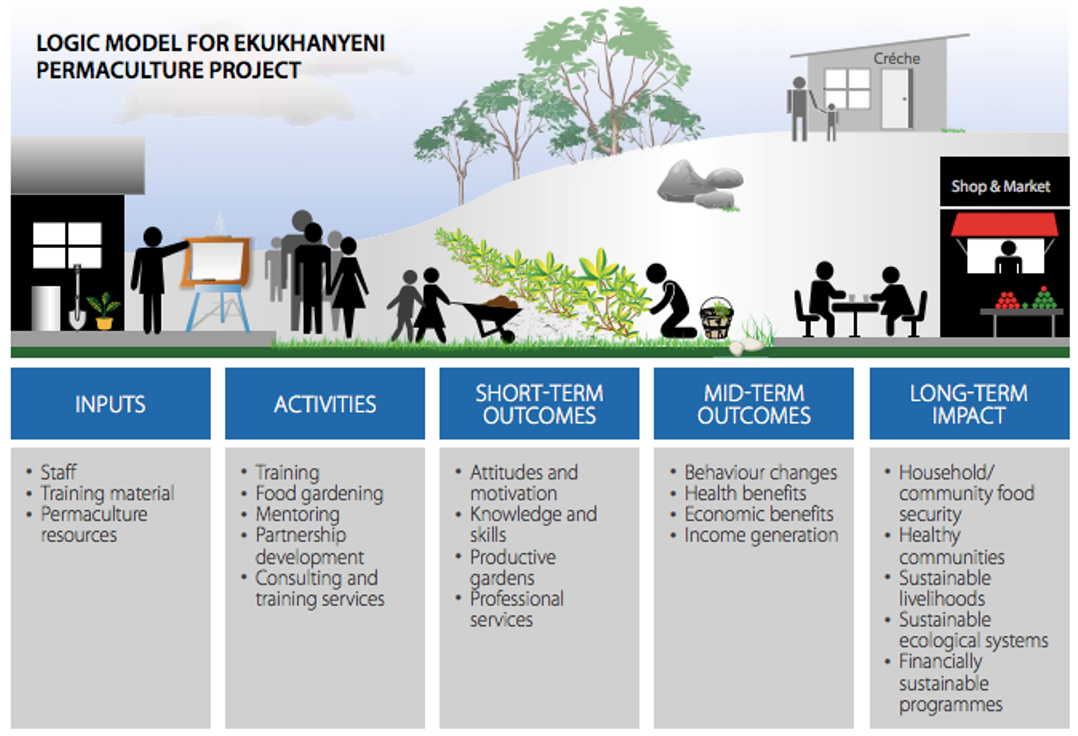

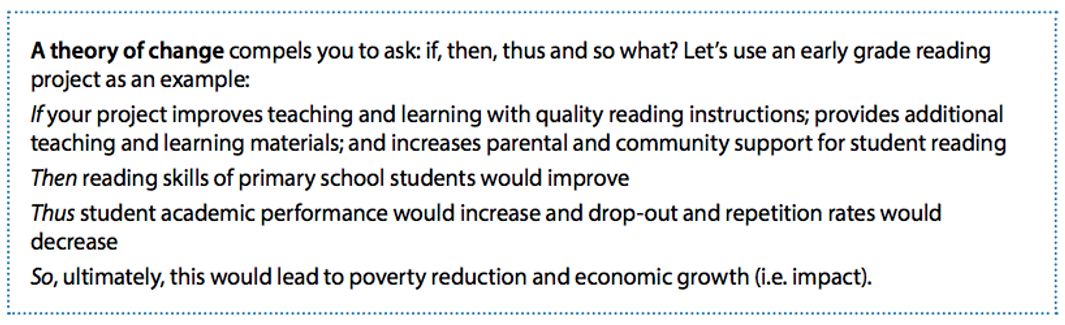

A theory of change depicts how a programme’s inputs and activities are understood to produce outputs – a series of short and medium-term outcomes and, ultimately, long-term impacts. Evaluation theorists refer to the theory of change as ‘the missing middle’: filling the gaps between what goes into and what comes out of a project. This is usually represented in a logic model, which graphically depicts the desired outcome of your project.

The logic model includes inputs (what is invested), outputs (activities and participants reached) and outcomes. It also documents the key assumptions in each step. In 2014, Khulisa developed an M&E framework for urban permaculture project Ekukhanyeni, taking them through a collaborative process of developing a theory of change and logic model.

One of the important criteria for developing a theory of change is that it has to be participatory and consultative of all stakeholders. Khulisa invites funders, project designers, managers and beneficiaries to talk about what they want to accomplish and what they believe will foster change. With the Ekukhanyeni project, the gardeners were actively involved in the development of the theory of change, building capacity and also helping to understand why M&E is important for the project’s future.

When resources are invested in an education programme, outcomes are anticipated. However, there are associated assumptions that need to be uncovered, and a chain of events required to take place, in order for those outcomes to be realised. An indicator is a simple way to measure a complex scenario.

For example, people often judge the quality of a high school by the indicator of its matric results. A good theory of change would add several other indicators to judge the quality of the high school and might include the turnover of teaching staff and the throughput (for example, is a student who starts grade 8 likely to complete grade 12 in the prescribed five years?).

Before a project starts, people usually have an idea of what they want to do and achieve. The theory of change tests the logic behind those ideas and, through the process, indicators are developed, which become the core of an M&E framework.

Data 101: If you can’t use it, don’t collect it

When a client starts doing M&E, they collect data on everything. The golden rule about data collection is that less is more. There needs to be clarity regarding which indicators to choose and the reporting process has to be as painless as possible. Once the indicators have been identified and the measures have been set in place to collect the data, feedback loops should be created to inform those who are collecting the data.

An M&E framework requires feedback mechanisms which show your data collectors that the data is being used to improve a project in specific ways. It closes the gap and it makes the data collectors feel that what they are doing is valued. It is important that everyone involved in the project knows what each piece of data is going to be used for. If the data collector does not understand the big picture, there is less motivation to provide accurate data.

The answers lie in fewer but more relevant data points, and this goes back to proving the theory of change.

In the early grade reading example, data should be collected at each link of the chain. If additional teaching and learning materials are introduced into the classroom, the first data point would be whether or not the books have been delivered and are in use. Only then can measurement occur regarding whether any learning took place.

There should be a logical link, or skip pattern, between data collection points.

Is your project ready for evaluation?

Once relevant data has been collected over time, it is possible to answer specific questions about the success or failure of a project. An evaluation is only as good as the person managing it. If the evaluation process is outsourced, it is critical for the evaluation questions to be explicit.

The best way for programme managers to keep a tight grip on this process is to develop a thorough, highly specific terms of reference (ToR). This is a useful exercise, even if an evaluation is undertaken internally. It is necessary to critically interrogate the data and monitoring system when developing a ToR.

If the monitoring system does not produce good routine data, the evaluation could become extremely expensive, since the evidence will need to be gathered from scratch, rather than merely being validated. BetterEvaluation.org, an international collaboration which provides excellent resources on how to improve evaluation practice, has developed a reference guide called GeneraToR. This tool helps programme managers to think through what they want, before commencing or commissioning an evaluation.

It’s not uncommon for an evaluator to discover that the programme is not ready for an evaluation during the evaluation. To prevent this, a school of thought now emphasises the importance of doing an evaluability assessment; this allows you to assess how far implementation has gone, whether there is a clear theory of change, and to ensure that routine monitoring data exists to use during the evaluation.

The evaluability assessment may either point to a need to strengthen a project’s monitoring systems; allow more time for the project to deliver; or give the thumbs-up for the evaluation to commence.

Which methodologies are most suitable?

M&E is a dynamic, ever-evolving discipline and new methodologies constantly emerge at international conferences.

Two things are important to note:

- Evaluation questions could be answered by adopting multiple methodologies.

- Clarity of outcomes is needed when choosing the most suitable method(s) for an evaluation.

If the theory of change has been approached in the right manner, these outcomes should already be clear. The methodology selected will depend on what it aims to achieve. If seeking an answer to ‘what works’, an experimental design, such as a randomised control trial or a quasi-experimental design, may be applicable.

There are, however, many other cost-effective methodologies that could also be rigorously applied. An evaluation could be done in a weekend. The appreciative inquiry, for example, uncovers stories about a project and could be done by asking stakeholders to share how the project brought tears – whether of joy or sorrow – to their eyes, or what difference the project has made to their lives.

These stories should then be verified, or impact stories could be gathered from which to build an evidence base. Always link the selected evaluation methodology with the desired outcome of the project. For example, a very different design would be chosen if the aim was to provide services to elderly people in an old age home than if the aim was to improve the quality of mathematics in South Africa. For the latter, the mathematics teacher training programme would need to be upscaled to ensure system-wide impact, and therefore the best results would be achieved with a quasi-experimental design.

However, if, in the case of the old age home, an assessment was being done on whether residents were receiving reasonable nutrition, intellectual stimulation, basic healthcare and protection, then an entirely different monitoring system, and therefore a different evaluation methodology, would come into play.

Standard operating procedures for the future

What does the future hold for M&E in the private sector? The best way to summarise it is with the acronym SOP. In organisational theory, a standard operating procedure (SOP) helps workers to carry out complex routine operations and aim for greater efficiency, quality outputs and uniformity of performance.

S is for ‘system-wide impact’

Companies are trying to spend money more smartly and are conscious of the fact that billions have been spent with little impact. There is a shift among companies to achieve systemic change through their interventions, which calls for more rigorous evaluations. Education in South Africa, for example, cannot be improved without addressing the interconnected elements: teacher training, school leadership, curriculum, the psychosocial and physical circumstances of the learners, and the classroom and school facilities. If an intervention concentrates on one detail of the system without considering the consequences, intended or unintended, of the other system links, it is less likely to succeed.

O is for ‘openness to share and learn’

There is a growing willingness among corporates to be open about their evaluation findings. There is a trend towards publishing more report findings, or at least some public exchange with the intent to share critical lessons so as not to reinvent the wheel. Learning and accountability are fundamental components of evaluation; objectives that are hard to achieve if companies are not prepared to admit to ineffective programmes and learn from each other.

P is for ‘presentation’

This third trend is to make evaluations less academic and more user-friendly, with the support of infographics, data visualisation and communication strategies that are appropriate for the stakeholders in question. If you are communicating with a board that has just 20 minutes to understand the impact of your CSI programme, you cannot give them a 300-page document. A shorter evaluation report does not imply less work, strategic thinking, or rigour in evaluation design. It only means that you took the time to make the findings digestible and understandable, which make them far more likely to be implemented.

Download the full handbook by following this link.

Really a worth reading article, I learnt a very good things to be consider during the course of any evaluation.

Will surely apply the learning in up-coming planned evaluations.

Keep doing the great Work.

Good Luck.

Best

Abid

Thank you Abid, we appreciate your feedback

Interesting article and I one fact I may point out is that programs/projects collect data that they eventually do not use. They fail to understand that it is not a must you collect every data but collect what you can use and depending on the resources the program has. Good lessons learnt in monitoring as well as evaluation from this article.

Best,

James

I agree James, I often preach that if you do not know how to use the data then DO NOT collect it…

This is indeed a great peace of knowledge on M&E. It is really simplified, direct, up to the point and digestible. Bravo to all those who contributed to this piece in one way or the other. Keep up the good work and enlightenment in the field of M&E.

Thank you so much Kebba, we are pleased that you found this article useful.

Although evaluation is retrospective in the sense that we measure, reflect on, and value findings, it is important that evaluations are designed prospectively. Too often, programme implementers and funders request an evaluation at or near the end of implementation. Good evaluation design is conceptualised alongside planning the intervention.

Thank you very useful article, I wish to participant in your workshop and share my skills and knowledge as I have several years experience in M&E.

All the Best,

Mahina