Khulisa, in partnership with the South African Department of Basic Education and the U.S. government, recently released a report establishing early grade reading (EGR) benchmarks in Tshivenḓa, one of South Africa’s 11 official languages. Tshivenḓa is the third South African language for which the Khulisa team has developed EGR benchmarks; since 2018, Khulisa also created EGR benchmarks for Setswana as a home language (HL) and English as a first additional language (EFAL).

Early Grade Reading Benchmarks for Tshivenḓa

Over the last five years conducting this important work, creating tools to improve the literacy skills of thousands of South African learners, the Khulisa team has been focused on the importance of learning to read in our society. We’re especially focused on giving the right tools to the teachers who carry this huge responsibility.

“Being a foundational teacher is so critically important for South Africa. You are at the core of transforming our country – of entrepreneurship, of economic growth, of our social development,” said Khulisa Education and Development Division Director Margie Roper.

Creating EGR benchmarks also requires careful study of how children learn to read, and, eventually, how children begin to read to learn. “If someone can’t read, they are excluded for life in so much of the world,” Margie said. “How do you program your phone, or access the news? How do you access information for the health of your child?”

During a recent team discussion during Literacy Month, our team members working on the EGR task orders in South Africa reflected on their own experiences – and their children’s experiences – of learning to read. Their experiences especially illustrate the challenges of learning to read in multilingual societies, where English is often given precedence over indigenous languages.

Learning to Read

“I was thinking back to how I learned to read, because as adults, we don’t actually think about how we learned,” Margie said. “We almost think that it’s automatic, but we forget that we actually went through the process of learning to read, and what did that entail?”

Margie, who grew up in South Africa and learned to read in English, kicked off the discussion with her memories of struggling to read as a child.

I’ve always struggled because I’m dyslexic. I can’t spell, so for me, the switch came much later in terms of being able to do reading for learning…The automaticity for me only came, I think, when I was in grade five, or six even, because of that. And I think all of us have learned in different languages, different systems, different styles.

Team member Tamar Boddé-Kekana, who grew up in the Netherlands and learned to read in Dutch and English, among other European languages, spoke about how she started to read by watching television shows with Dutch subtitles. Ayanda Lindsey, who grew up in Soweto and learned to read in isiZulu and English, started reading in church – singing hymns in her isiZulu hymnal and matching printed words with the words she sang.

Thembi Mahlangu shared her experiences learning isiZulu and English in South Africa’s Mpumalanga province.

I’m from Mpumalanga in a town called Embalenhle. Our teachers would normally just say things in isiZulu first before they were said in English. And sometimes we didn’t get the real language because we were always trying to directly translate isiZulu into English. Sometimes it became worse to a point where the teacher would just explain something in isiZulu and we were supposed to write it in English.

So those are some of the limitations…And when you get to varsity [university], you’re struggling with the language…You struggle to comprehend and to be able to read.

Tshandapiwa Tshuma shared a story about her daughter’s process of learning to read in her home language.

She started by learning to speak isiNdebele because that is the language that we spoke at home. Eventually she had to go to preschool, and the language of learning and teaching at preschool was English. She mastered English and l let her be because l thought l would disturb her English language development if l started to teach her how to read in isiNdebele.

When she proceeded to primary and high school, the language of learning and teaching was English…Eventually l got worried when l sent her messages in isiNdebele and she would call back and say, “Mama, l can’t read your messages.” l realized that this would be a problem…and l had to start teaching her to read isiNdebele when she was in Grade 10. It was not easy at first – l made sure she mastered the sounds, then syllables followed by words, and eventually she started joining them together. She still can’t read some difficult words…Now l believe that she should have learned to read both languages and they would not affect each other. She is missing out on some deep isiNdebele written stories and messages.

Our team members’ diverse range of experiences illustrate how much language matters in the way reading is taught.

Looking Forward

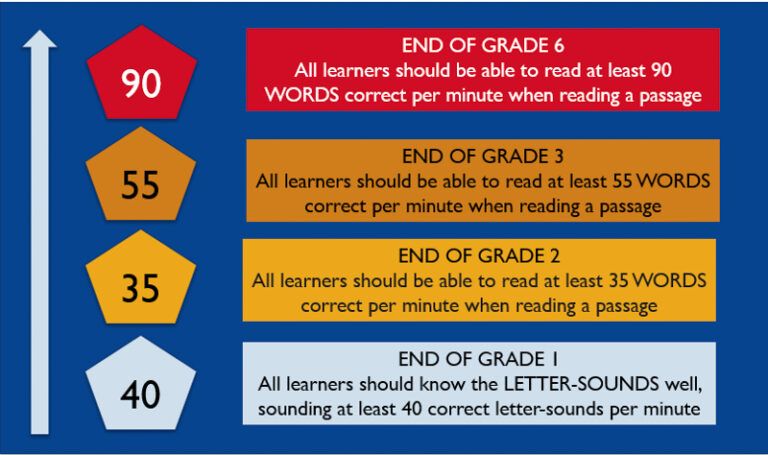

The Tshivenḓa HL benchmarks should be integrated into a national system for monitoring early grade reading skills. The benchmark database can further be increased by conducting early grade reading assessments in Tshivenḓa. In addition, training and equipping educators to interpret learner assessment results and use benchmarks will enhance early grade reading and literacy in South Africa.

Having created reading benchmarks in three South African languages – assessing more than 10,000 students in 574 schools and surveying more than 1,700 teachers – we now know more than ever before about how to create reading benchmarks and how to teach learners to read in African languages. Khulisa is proud to be part of expanding this important research and knowledge, hopefully beyond the borders of South Africa, and helping equip teachers to prepare a new generation of readers